Photo Diary: YA English Creative Writing class

Sunday, 23rd of October 2022

Written by Fairuza Hanun

Today, the sixth batch of Level Writer students — and the fourth batch to ever advance immediately to Level Writer after their entrance exams — discussed lessons of descriptive writing, and how it is inseparable from the political aesthetics and practices of poetry. After an introduction to literary techniques and how they can be used to empower writing, I bridged the lesson to our previous one about world building and memory, to prompt in them how natural landscapes and emotion are interminably connected. To demonstrate that, I used pieces from diverse sources of literature, including poems from “Glacier Line” by Kári Tulinius (translated by Larissa Kyzer from the Icelandic), “The Rain Horse” by Ted Hughes, and briefly touched upon nature-affected works of such as Yu Miri, Yoko Ogawa, Amitav Ghosh and Yasunari Kawabata which they could explore.

Each student took turns reading out stanzas from Kári Tulinius’s poems, learning to feel the lines with each breath and pause, and to consider every word choice. Out of the reading, we briefly discussed together the themes, effects and reflections evoked by the poems, and each student had something different to say — an interpretation that is unique and characteristic of them. Naf— and A—, who respectively has done literary analysis at school and have been raised with a critical thinking system at homeschool, both offered that the first poem, “Vanishings of Snæfellsjökull Glacier” resonated loneliness in a landscape of loss, as well as a kind of isolation which can be felt by the only one who notices a loss or a disappearance, tethered by a sense of intimacy. Nay—, who at the first mention of poetry in class had announced her dislike/indifference to it, proposed straightforwardly that it describes a bleak landscape and said there were a couple of lines that struck her as humorous. Already it was intriguing what they had to say, despite it only being a warm-up to the following activities. Next, I asked them to choose a favourite stanza of theirs from said poem and sketch the image that they experience through their reading of said stanza. Once we shared the pictures, I asked them to read the second poem “Upon seeing Snæfellsjökull Glacier from an idling bus” and write a reflection comparing the two poems.

The fact that these students, young as they are, are realising these deeply impactful connections between nature and emotions, particularly qualities which signify our personhood, gave me hope that they could recognise and document more of these changes happening to the micro-landscapes in their daily lives. How environmental disintegration is occurring before our eyes, shifting even the particles in the air we breathe, in the components and density of the soil beneath our urban asphalts and concrete. I prompt these discussions with them so that climate intimacy and awareness are woven into more fiction writing, as Amitav Ghosh urges us to do. As Tulinius wrote, ‘poetry documents landscape’, we need to document more of our landscapes which we take for granted, before they disappear, too. Words stay when everything else dwindles.

Image description: A worn sail upon a broken mast floats upright and yet without the foundation of a ship. Pieces of wood from the mast are sinking into the sea, suggesting the seemingly subtle yet rapid disintegration. Thick mist contains the word LOVE and one half of a broken heart, of which the other half has fallen and begun its sink towards the bottom of the ocean.

Naf— wrote and presented in class with several oral improvisations (retained in brackets): “These poems address nature and the environment. Firstly, the poem “Upon seeing Snæfellsjökull Glacier from an idling bus” addresses nature in a way that it speaks up about what we see during climate change or what happens to [the glacier]. It talks about what you find after the snow melts and states that the glacier will be ‘tossed in a garbage can,’ suggesting that it will not be cared for anymore and treated as though it is nothing. The other poem [“Vanishings of Snæfellsjökull Glacier”] also raises awareness about [climate change’s effects on the glacier], showing how the glacier can vanish and using symbolism to speak about the matter, such as in the first stanza. This poem focuses more on how the glacier can symbolise many different things, mainly showing how the environment lives and how our love towards it is vanishing, putting [love’s absence] in a negative light. The best lines in the poem are: ‘love vanishes in clouds / and crumbles’. This is because originally, before that line, the writer states how love only crumbles or only sinks. However, [they emphasise a refusal or perhaps a reconstruction of their thought by pitting a line of a single word — ‘no’ — between these two concepts]. In [the quoted] line, it illustrates that love firstly disappears, it is gone before it can be turned [into a negative thing]. Love, the feeling of love or care has to disappear first before it could be permanently or destroyed or turned into another emotion. [As for the best phrase in “Upon seeing Snæfellsjökull Glacier from an idling bus”], the lines ‘2) snow melts / becomes a mountain that is a mountain’ are intriguing because it could be interpreted in a way that when snow melts, the mountain [of ice] will lose its uniqueness [and become just another mountain]. When climate change happens, many landmarks will be destroyed, turning them into the ordinary. Erasing their sense of wonder.”

Image description: In an abstract drawing of bold lines and swirls, they seem to depict heavy, thick mist which is shrouding a celestial body in the sky and is surrounding the glacier, covering the sea. The glacier at its centre appears stumped and unremarkable, its points having tapered off as testament to its significant melting. To the glacier’s right, there is a ship so small that its size is inconsequential to the glacier, yet this is countered by the ghostly humanoid figure which holds what appears to be a single flame in their hands. On the bottom right corner, a large square containing smaller squarish shapes and a large humanoid silhouette, seem to depict the author’s sitting in an idling bus during their observation of the glacier.

A— wrote points and largely improvised her presentation in class, transcribed as: “My mind really did lag while reading these two poems. There were parts of the poem where I could imagine the scenery and landscape and I could feel a sort of sad, calm emotion, as if I’m watching something precious disappear from the world but all I could do was stand there and watch. The glacier in my interpretation symbolises love in some way, from the March and April stanzas. Both poems bring up the effect of climate change towards our environment, specifically ice glaciers that are slowly melting and how a majority of people don’t bat an eye just because they believe that this situation won’t affect their current life, so they let glaciers crumble and disappear until they realise too late that this could have been prevented. This is something I’ve seen happen often in relationships. The lines ‘love sinks / love crumbles / no / love vanishes in clouds / and crumbles’ and ‘only in disorder / do forms resolve / the sea is a line that divides / love from love from time’ from the second poem is what made me think this. Another mention of climate change is in the first poem. I think the line ‘Snæfellsjökull will be tossed in a garbage can / disintegrate among banana peels / paper cups soda cans candy wrappers / garbage that is garbage’ describes how the existence of glaciers will be tossed away and forgotten like garbage, and will melt into an ocean filled with paper cups, soda cans and candy wrappers.”

Image description: The sketching is broken down into mini sketches to depict each interpretation of each line in the chosen stanza. The first sketch shows a picture of a quotidian landscape with grey shadows growing behind it. The second one is of a breeze sending the picture away. The third one is a digital camera. The fourth one is a stickman embracing the picture. The fifth one is a skirt worn around a pair of legs, fluttering in an invisible breeze. The sixth one is of a veil crowned with flowers being lifted away by the wind.

Nay— wrote and presented in class with a couple of spoken corrections (retained in brackets): “I think the themes of the poems are related to the glacier and nature, although it [also contains other] aspects of life, [such as] love and the little things in life. There might be a connection between landscape and emotion in the poems because the author wrote it while observing the landscape [in their attachment]. The poems talk about the glacier in a very poetic way. Shapes, figures and colours are used to emphasise and personify the glacier. I think those choices make the poem more artistic. For me, the best lines in the poem are: ‘see a sea yes / see mountains yes’, because I think they’re funny.”

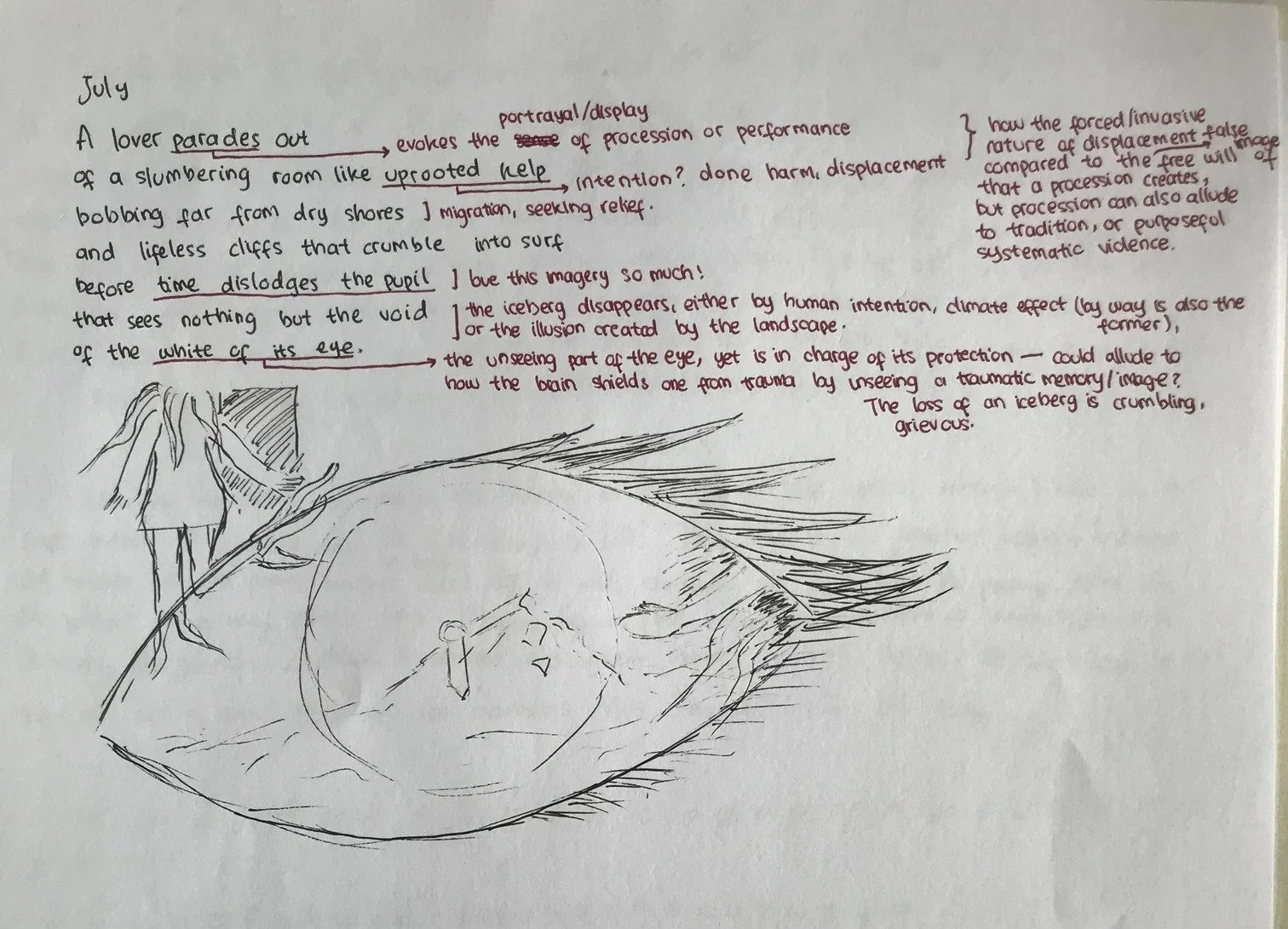

Image description: In the top corner, a humanoid figure with kelp hair and kelp limbs exits a dark room. The centrepiece is a large left eye whose pupil is replaced with ticking clock hands; the long hand is in the middle of crumbling, its pointed tip once part of the glacier peak, so that each minute represents a piece of the glacier vanishing into the deep ocean, and the short hand points at the waters, suggesting finality of gravity. Taking up the expanse of the sclera and cornea is the vast sprawl of the glacier whose whiteness blends with the sky and the sea, thus its existence and absence appear to be interminable without beginning or end. In the corner tip of the eye, a hand which also looks like a kelp reaches out of the darkness.

I made sure to participate as well, because I have learned from experience that a demonstration eases nerves of upcoming presenters. I demonstrated this by responding to the July stanza from “Vanishings of Snæfellsjökull Glacier”: “The poem contains vignettes of observations of the glacier by the author during each month when the opportunity was presented to them. The various effects expressed in each stanza portrays the fickle emotional relations of the author to the glacier, although consistently tied with a theme of loneliness, helplessness and evaporating love. Love particularly is most prominent throughout the poem. The first two lines in the July stanza, ‘A lover parades out / of a slumbering room like uprooted kelp’, evoked two possible interpretations. A parade suggests procession or an elaborate, ostentatious, often festive performance, yet ‘uprooted kelp’ in the second line creates the impression of intentional displacement. They may be proposing that the lover, who I firstly interpret as nonhuman being, has been the object of forced/invasive practices, which are considered tradition — a systemic violence — at this point in anthropogenic times. Thus, their aimless drifting away ‘from dry shores’ and from the ‘lifeless cliffs’ of the glacier feels similar to an act of migration or even asylum, for a missing destination, absent of relief. The other interpretation is that the lover is human, proceeding out of love, ‘uprooted’ due to their loss of sense of place and belonging among nature, a willful extraction of self as they abandon the glacier. Soon after either interpretation’s departure, ‘time dislodges the pupil’, as if removing the eye from properly witnessing the glacier’s slow demise, replacing it with ‘the void / of the white of its eye’. The latter could allude to the glacier’s disappearance by either human intention, a climate effect, or it could be the illusion created by the icy landscape. But it is also important to note that the white of the eye, also called the sclera, is in charge of the eye’s protection. It may evoke protection? The way a brain inhibits access to a traumatic memory, and it makes sense considering climate loss is grievous.”

Names are purposely omitted to protect students’ privacy.

Texts used in lesson:

from "Glacier Line" by Kári Tulinius

"The Rain Horse" by Ted Hughes

"North Winds Blow the Leaves from the Trees" by Yu Miri